A Journey to Shangri-La

Text: Paul Lee

Photographs: York Liao

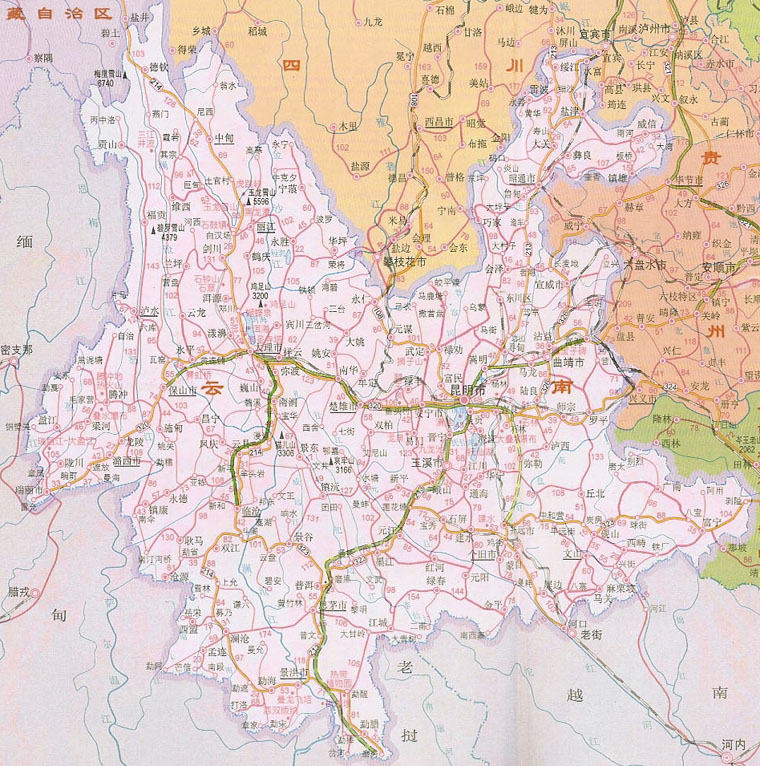

Note: a list of the Chinese names and a map of Yun Nan are provided at the end of this article

When our plane landed, we could see the shining words at the terminal. It was official. We were in Shangri-La.

When James Hilton wrote “Lost Horizon” in 1933 and introduced the Tibetan utopia, he was looking for a place of retreat from modern civilization, particularly the horrors of World War I. The inspiration for the locale came from the Austrian explorer Joseph Rock. Rock started learning Chinese on his own when he was thirteen. After high school, he took leave of his angry father and explored the world on his own. He ended up spending twenty-seven years in the Yunnan region of China and made some pioneering studies on the Nasi minority. His published a series of his observations in “National Geographic” in which he mentioned a magical mountain. This became Karakel in the novel.

“But it was to the head of the valley that his eyes were led irresistibly, for there, soaring into the gap, and magnificent to the full shimmer of moonlight, appeared what he took to be the loveliest mountain on earth.” (“Lost Horizon”, P 57).

To see this lovely mountain was the main reason for us to be at Shangri-La.

Shangri-La Region

At the northwest corner of Yunnan, there is a region where three mighty rivers, in close proximity, tumble down from the Tibetan Plateau. They carved out deep gorges overlooked by lofty snow peaks. It is a beautiful and remote region. Officially, it is called the Di Qing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and consisted of three counties: Zhongdian, Deqin and Weixi. In 1997, Yunnan officials announced that this region is the Shangri-La depicted in Hilton’s novel. They pointed out a list of familiarities which made the claim plausible. In 2002, they narrowed down the region and renamed Zhongdian County Shangri-La County and the County seat is now called Shangri-La. This last step seems to reflect the prowess of Zhongdian as a political entity rather than its natural allure.

Snow mountains abound in this enchanted region. Between Jin Sha (which would turn east to become known as Yangzi River, also known as Chang Jiang, the longest river in China) and LanCang (Mekong River), there is the BaiMang Snow Mountain. Further west, between LanCang and Nu (Salween) lies the MeiLi Snow Mountain. Its magnificent main peak, Khawakarpo (22,113 ft) is the highest peak in Yunnan. This mountain range has thirteen peaks and is the most important of the eight sacred mountains for the Tibetans. This is the goal of our quest.

Zhongdian to Deqin

Our friend, How Man Wong, has worked for thirty years in the remote regions of China as a photographer, writer, conservationist, and explorer. He is the president of CERS (China Exploration and Research Society) and established a center in Zhongdian for his myriad activities. He had arranged for a car and driver to take us to the Sacred Mountain. We went to bed early to get acclimated to the 10,000 ft altitude and ventured north the next morning.

We started around 8:30 and took highway 214. Our driver, A Ya, was an experienced driver who kept his old four-wheeled drive in top condition. The road was carved out of the side of high mountains with constant threat of landslides. There were no guard rails between our car and the thousand feet drop-off. It is absolutely necessary that both car and driver were reliable. If you could take time off from watching the road, you would see the amazing view of mountains in every direction with lush forests and an occasional group of houses hugging the cliffs.

Around eleven, we came to BunZiLan. This little town was an important stop on the trade route between Yunnan and Tibet. There were some newer establishments in this thousand-year-old town. We stopped for lunch at a three month old hotel/restaurant. Three bowls of noodles with meat and vegetable came to be less than $2.

After BunZiLan, we came to a spot where Jin Sha River made a hemi-circular arc. It would travel further south until it reaches LiJiang before it turns east. Legend has it that the three rivers were three daughters who were seeking their loved ones in the east. Their parents sent their brothers down to stop such wanton behavior. Two of them were blocked but the third one made a semicircle as a feign and then made her way east to become the Yangzi River. Until we hear something better from the geologists, we have to accept this explanation.

The road was now unpaved and bumpy. We caught a nice view of the BaiMang Snow Mountain. Then we hit a big shower which lasted one hour. This kind of weather is quite common at this time of the year. As we headed north, we were climbing mountain after mountain. Sometimes the scenery would hardly change because we were following long switch-backs to go up a mountain. This mountainous regions was a strong deterrent to intruders. Genghis Khan broke through the great wall of China with little difficulty. His grandson, Kublai Khan rode into Yunnan and took twenty-seven years to subdue the fierce natives. There were no more towns until we got to Deqin, just an occasional shed that was home to a Tibetan shepherd. We went through a pass at 14,527 ft and descended into the Deqin valley. (Hilton mentioned Tat-sien-Fu in “Lost Horizon” which could be Deqin.)

Just outside Deqin, we stopped at the viewing terrace near Fai-Lai Temple. On a clear day in winter, this would be an excellent place to see the MeiLi Snow Mountain. However, the elusive mountain was completely hidden behind the clouds. York made the pilgrimage two years ago and spent ten frustrating days waiting out the rain. He did not see any trace of the mountain. We hoped for better luck this time though statistically speaking, the odds were against us.

Our destination for the night was the Xidang Spa. To get there we have to go pass Deqin until we were about sixty miles from Tibet. Then we leave the highway and started on a road that wound down the steep mountain slope. We crossed the raging LanCang river and traveled up the mountain slope on the west side. Here the road was treacherous. We were also near the scene of a recent tragedy. A young teacher who had come from the city to teach in the local village was in a car that plunged into the river. The occupants of the car perished in the raging water. At death he became a national hero even though his real heroism was what he did in his short life.

We went through the little village Xidang and arrived at the spa hotel at the end of the road. We secured a room at $5 for the night. It was Spartan but was relatively clean. Our driver, who turned out to be rather particular with his food, directed the chef to cook us a chicken. The chicken came out in a big basin. There was another basin of mushrooms and vegetables. We washed it down with beer that had been cooled in the nearby stream.

Xidang to Yubeng

Now we were close to our goal – Yubeng village at the foot of the MeiLi Mountain. All we needed was good weather and the stamina to make the climb. We woke up to a cloudy sky but at least there was no rain. We hired a horse and a guide. We needed some help to carry our bags and I took advantage of the sturdy animal to carry me up the mountain. Starting at 7000 ft, we had to go up to a pass of 12,600 ft before descending to our destination. Climbing 5000 ft at this high altitude was not an easy task. The path was steep, the rise being on average one in seven, and muddy so I did not envy York who was on foot most of the time. After one hour, I arrived at a roadside tea stand. There was a group of Tibetans out in force looking for SongRong, a kind of mushroom. It was the first plant to grow in Hiroshima after the atomic bomb and enjoys a almost mythical position in the Japanese diet. It has to be teased out of the ground like truffles and its high price helps the local economy. York arrived in another fifteen minutes, providing a data point for the difference between horsepower and human-power. The steep climb and the high altitude were more difficult than he remembered. There were two young women from GuangDong (Chinese province north of Hong Kong) who were hiking with their heavy backpack. One of them was surprised to find out that York had hiked this trail two years ago. If ever she came back again, she said, she would definitely opt for the horse.

The next stretch continued to be muddy and steep. We were in a forest area with very little human traffic. A woman was in charge of the second rest stop about another hour away. She was offering the Tibetan tea, boiled tea mixed with Yak butter and spice. York ordered a few cups. Remembering How Man’s remark that he threw out twice as much fluid as he took in when he partook this concoction, I refrained from being adventurous. It was now about 11:30 and we took out the compressed biscuit and a can of luncheon meat that we bought at the inn. The compressed biscuit was somewhat similar to wood that had been softened by termites but it turned out to be our main source of nourishment since the luncheon meat was not edible. There was no resemblance between its contents and any part of any species in the animal kingdom. Later, we were able to ascertain that the can we bought was a counterfeit!

After the second rest stop, I traded places with York. The ground was less mushy and it was quite pleasant walking this short stretch. When we arrived at the 20,000 ft pass, there was another roadside stand. A friendly man served us hot water. He was recommending the Hiker’s Inn as the place for us to stay at Yubeng.

After the pass, the sky suddenly cleared and the peaks of the MeiLi Snow Mountain appeared magically. We could see a large part of the main peak, Khawakarpo; the group of four rugged flat structures at 18,000 ft and the majestic 19,862 ft Me-Tse-Mo. We rejoiced in our good fortune and marveled at this grandeur. Then the path turned and the mountain was hidden but we knew what could be in store for us at Yubeng if the good weather continued.

From here on the path going downhill was fairly steep, too dangerous to ride on a horse. Another hour later, we got to Yubeng. There was an upper and a lower village with about 150 inhabitants. The houses were nestled in a green valley. There were lush green mountains on all sides and the majestic Me-Tse-Mo towering at the west. This was indeed Shangri-La!

Yubeng

The Hiker’s Inn was situated between the upper and the lower village and commanded an excellent view of two peaks. The proprietress was a young woman and showed us a very clean room at the second story. The hotel was so new that the stairs to the second story was not yet built. We had to go up some steps hewn on the mountain side and walked across a 3 m gap on two planks of wood. Any reservation we might have about the inn was dispelled as soon as we looked through the windows of our room. We could see the lower village in the green valley with the conical shape of Me-Tse-Mo at the back. A low hill in the middle blocked the lower peaks but right next to it was the southern end of the main peak. It was simply fantastic.

The rate for our room was $6 for the night. It must have the highest ratio of view/dollar any where in the world. We had to tear ourselves away from the window to explore the lower village.

To reach the lower Yubeng, we went down the steep hill, crossed a bridge and then walked up the slope. The village was very quiet. We saw two old women outside one of the houses and a man near a house being constructed at the end of the village. Going beyond we could take a three hour hike to the “Sacred Fall” where water from the sacred mountain came out in a 1000 m drop. We were too tired to make this pilgrimage and contented ourselves with admiring this idyllic village.

Back at the Hiker’s Inn, we met some fellow guests. Five avid photographers from Sichuan staked out their places in tents on the second story patio so that they could photograph the moon-lit mountain. There was also John, an American who was working as a member of Peace Corp at Kazakhstan. He did not know Chinese but was able to make his way to Deqin by bus and hitched a ride to Xidang on the strength of body language.

A young teacher, Ms Liang, who came from Kunming and had taught for six months at the local school with nine pupils, was at the premise as a guest cook. She cooked us a noodle dinner with eggs and tomatoes.

The scene of the village and the snow mountain was enchanting in the moonlight. While we were reading in our room, John knocked at our door and asked us how to turn on the light since he could not find any switch. We told him to screw the light bulb all the way in and felt justifiably proud of our Caltech education.

MeiLi Snow Mountain

Next morning, over the simple breakfast of plain congee, Ms Liang told us that she will be taking her pupils to clean up the debris at the base camp from previous attempts to summit the peak. She was a dedicated teacher who wanted to instill respect for the environment to her young charge. We also talked about the attempts to scale this sacred mountain.

So far, MeiLi’s main peak, Khawakarpo, has not been conquered by human. The closest attempt got to within 270 m of the summit. In December, 1990, a group of Japanese and Chinese mountaineers set up a base camp at 15,000 ft. From this point on, the mountain was too steep for animals. They made steady progress and set up three advance camps reaching 20,000 ft. The weather was fine and they decided to attempt the summit. Ten thousand people gathered at the Fai-Lai Temple to witness this event from across the gorge. Then the weather changed and they were forced back to the third advance camp on January 2nd, 1991. All seventeen climbers perished that night when an avalanche hit their camp, making it the second worst mountaineering tragedy in the world. A memorial plaque had been erected near the Fai-Lai Temple to commemorate the fallen mountaineers.

The last attempt to scale the mountain came in 1996. A very experienced group of climbers from China, Japan and Nepal made the attempt. Before the climb, they went to the memorial plaque and pledged that they will carry out the unachieved dream of the fallen comrades. They got up to a height of 20,830 ft and were beaten back by bad weather. Afterwards, they went and knelt at the memorial plaque and broke down crying. The Japanese delegates announced that they had been beaten by the mountain and would not mount any more attempts.

We settled out modest bill with the proprietor, A Na Zhu, who had returned the previous night. After some casual conversations, it turned out that he was the owner of the house that York stayed in two years ago. Tibetans are very hospitable and this recognition made us old friends now. He told us about his family and the efforts he put in to build this inn. As part of his improvement program, he was installing a washing machine. On the previous evening one of his assistants carried the machine on his back over the route we took. Watching the fellow coming into the inn with his load on his back, John, our American friend, thought that the carton must be empty. We verified the contents and were still incredulous.

A Na Zhu also told us a legend about the founding of Yubeng. Some one had found a secret path to this village. He tried to eke out a living with farming but had a hard time with it. He would go to the larger village and borrowed grain each year. After a couple of years, he still needed to borrow grain but was secretive about the location of his homestead. His lender gave him a bag of grain but made a small hole in the bag. The lender was able to follow the fallen grains until the track stopped in front of a rock. After the rock was moved, he found the secret path to the hidden valley which became the Yubeng village.

Back to Civilization

After we said goodbye to the people at the inn, we retraced out steps. The most difficult part was the climb from Yubeng to the high pass. The weather was no longer as nice. When we met up with our driver in the afternoon, we could have gone north to visit the glacier coming down from Khawakarpo. But staying another night without toilet did not sound very appealing and we started on our way back to Zhongdian.

Back at the CERS center, we stayed for a few more days and enjoyed the hospitality of How Man and his wife Chen Li. The weather reverted to the usual rains and the mountains were shrouded in cloudy sky. Our two days at the mountain were the only two clear days during our entire stay. We could not be any luckier. We then flew back to Guangzhou (Canton) and landed at the new airport during the second day of its operation. It took us an hour and a half to find our luggage. We were not unduly upset. After all, we had left Shangri-La and were back to civilization.

Chinese Proper Names used in the article:

Di Qing 迪 慶

ZhongDian中 甸

Deqin德 欽

Weixi 維 西

Jin Sha 金 沙 江

LanCang 瀾 滄 江

Nu 怒 江

Khawakarpo卡 瓦 格 博

BunZiLan 奔 子 欄

Bang Mang Snow Mountain 白 茫 雪 山

FaiLai Temple 飛 來 寺

Mei Li Snow Mountain 梅 里 雪 山

Xidang Spa 西 當 溫 泉

Yubeng 雨 崩

Song Rong 松 茸

Guang Dong 廣 東

Me-Tse-Mo 面 茨 姆